The following is an adaptation of a report I wrote on the Minecraft AI agent I build as part of the final project for my Artificial Illigence class at UGA. Some parts of it still sound like a report.

Introduction

Minecraft (1) is a popular 3D open world that allows players to mine resources and the use those resources to build structures like houses and farms.

The game feature two main play modes: survival and creative mode. Survival mode is the default game mode; it requires players to mine resources before they can perform tasks and places enemy entities in the world. The creative mode is similar to the previous, with the exception that every player has access to all resource and can build anything they want freely.

Due to how the game is designed, performing some tasks in the survival mode requires a certain amount repetitive work. Before being able to build or craft objects, the player has to look for resources and materials needed to build a certain object. In addition, placing materials in the world to build structures requires the same keystrokes to be repeated many times.

The purpose of the project is to explore whether it is possible to build an agent capable of surviving in the game’s environment and assisting other players by collecting resources for them, and perhaps even building certain structures for them.

Initially, it would seem that simple program with some predefined macros would be able to perform such tasks in game. However, when the game is in survival mode, terrains aren’t flat and there are creatures that will attack the player on sight. As a result, agents looking to interact with the Minecraft world need to be able to react to game events and respond accordingly in top of also executing the task requested.

The game world

If you have played Minecraft before, you can probably skip this part

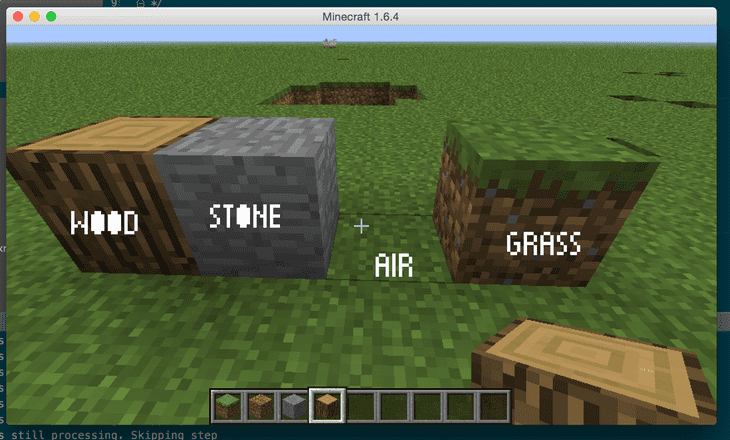

The Minecraft world can be described as a digital Lego set. The world is a practically infinite three-dimensional matrix. Each unit in the matrix is referred a voxel (a 3D pixel, cube). Each voxel can be assigned a type value, which indicates whether its air, dirt, grass, or any other material supported in the game.

Before the game server starts, a terrain is generated by randomized algorithms which generate different environments by assigning values to voxels. The generator algorithms try to generate different biomes by altering some properties depending on the geographical location.

There is also a day and night cycle in the game, which could be an important factor to consider when building an agent due to the fact that the game server will spawn monster or enemy entities at night, and kill them when the sun rises.

Using definitions from the Chapter 2 in the book (6):

- Partially observable: An agent is not capable to sense the entire state of the environment. This is due to the fact that the game server never sends the entire world data to the clients.

- Multi-agent: Other agents are capable of logging in into the game server. Depending on the agents connected, the environment can be competitive, cooperative, or both.

- Stochastic: Actions of an agent do not determine the next state of the game world since there are multiple agents and game entities interacting with it.

- Known: The outcomes of actions can have predictable probabilities.

Agent design

In order to simplify certain aspects of the design of the agent, I decided to divide the agent into three main components:

- Event handling

- Knowledge Base

- Task Tree: A multi-level priority queue capable of describing complex task hierarchies

Each one of the components loosely represents the concepts of Percepts, Reasoning, and Actions. The learning aspect was not included in this agent, but it would be an interesting case to consider in the future.

Components

Event handling

The event handling components acts as the Percepts of the agent. It receives events and information from the game engine and applies handler functions that input the information into the Knowledge Base component.

Information captured from these handlers is usually a boolean value such as or .

Knowledge Base

This component is essentially a simple key-value store accessible throughout the context of application. Additionally, this is paired with a rule engine, which continuously applies a collection of rules, which can modify the state of the Knowledge Base or queue new tasks to be performed.

Task Tree

The task tree is perhaps the most complicated component of the agent. It is capable of keeping track of tasks that the agent needs to perform, the progress of each task, the dependencies for each task, and the priority of each task.

Each task is subdivided into steps. Simple tasks can take only one step. Synchronous tasks also use one step but mainly since they need to finish before the bot can perform other tasks. Other tasks are more easily compost lie and can be divided into multiple steps.

As described before, the tree keeps track of tasks dependencies. Each task can contain a certain number of subtasks, which is what gives the data structure its tree nature, where each node is a task and its children are subtasks. However, reference to child nodes are not kept in a simple array, we use a priority queue which organizes tasks on their priority value (which can range from 0 to 100)

Main logic loop

The main loop in the agent run infinitely and performs the following two tasks:

- Process knowledge base rules based on the current state of the Knowledge Base

- Execute one step in the task tree (if any tasks are scheduled)

Events and game messages are sent asynchronously by the game server so they should be handled as they come in. When this happens depends on the implementation (single vs multithread).

Implementation

Language and library choice

For this project I decided to use Node.Js (Server-javascript) both because there is a preexisting interface for interacting with the game and it is a language I’m confident using.

The client interface is package called Mineflayer (2). The package implements most methods used by a Minecraft 1.6 client, so it is able to connect to game servers like any other player would.

The package also provides a good amount of interfaces for querying the state of the world, the state of the player, and the state of other nearby entities.

For this reason, I won’t be using the knowledge base component as the sole source of information. In more abstract terms, the actual knowledge base of the agent can be thought as a combination of the variables provided by the client package and the internal KB component.

High-level programming

A benefit of using the Mineflayer package is that it implements certain essentials algorithms such as navigation and block finding (finds voxels of a certain material). This allows me to focus on programming higher level features such as logical reasoning and task scheduling.

In addition to Mineflayer, I’m using the following packages:

- Navigation (3): Implements in Mineflayer

- Scaffolding (4): Uses the navigation package but it also digs or places blocks to reach a certain target

- Block finder (5): Locates the nearest block made from a certain material given a reference point

Implementing the agent components

Event handling

Event handling was relatively easy to implement since the Mineflayer package provided an interface for listening on events. Example:

bot.on('move', function() {

// Handle move event here

});Knowledge Base

The storage knowledge base was implemented using a HashMap class (check FactCollection.js on the source code for the complete implementation), which pairs a string with an object. For most variables, I used booleans, but I also allowed other object types to allow the KB share information with Mineflayers. Some of this objects are references to game entities and blocks, which contain useful information as health and position. Example:

app.kb.facts.setTrue('UnderAttack');

>>> void

app.kb.facts.has('TargetPosition');

>>> false

app.kb.facts.remove();

>>> voidThe reasoning subcomponent was done using a rule engine, which loads all rules defined inside the src/Rules directory, and continuously applies them against the FactCollection.

As an optimization, each rule is capable of specifying which facts need to be defined in order to even be considered. Once the set of rules has been narrowed down, we check which rules should execute, again by using another custom function on each rule.

As a result each rule contains at least the following components:

- getDependencies: returns an array listing required facts

- isApplicable: returns a boolean saying whether or not the rules should be executed

- execute: executes the rule, which can modify other facts in the KB or queue tasks

A possible future alternative would be to create or use a logic language to define rules (e.g. First Order Logic), since the current approach is more comparable to a brute force approach to writing rules.

Task Tree

The task tree was implemented using pointers (or references) and simulated queues using arrays. Each BotTask node has a subTasks array which keeps references to the child elements of that node.

The step method in the taskQueue uses the subTasks array in each array to determine which task should be performed next or which should be continued. Queues (and Priority Queues) are not natively available in JavaScript so they are simulated by doing a stable sort by priority value on the array. This partially keeps the order in which tasks where added and gives priority to tasks with higher priority values.

Tasks implemented:

Tasks are available under the src/Tasks directory:

- Attack: Attacks a target entity

- AttackNearest: Attacks the nearest entity

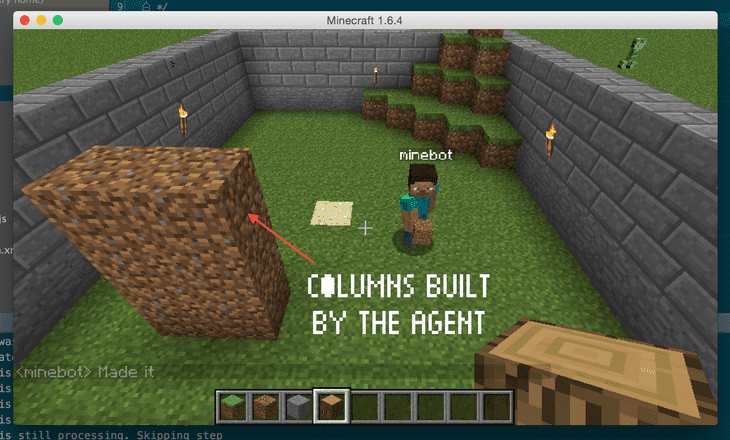

- BuildColumn: Builds a three block column made of dirt

- Chat: Sends a chat message

- DigBlockFromSite: Digs a block from a defined dig site

- DigBlocksFromSite: Digs multiple blocks from a defined dig site

- DigBlock: Digs one target block

- EquipBlock: Equips a block on the player’s hand (if any)

- FindNearestEntity: Find the nearest enemy entity and record it in the KB

- FindTargetBlock: Find the nearest block of a certain type

- JumpTask: Makes the agent jump once

- NavigateTask: Navigates to a target point using the scaffolding plugin.

- PlaceBlockUnder: Places a block exactly under the agent by jumping and placing the block

- StareAtTask: Makes the agent stare at an entity (player, enemy)

Results

Behavior of the agent

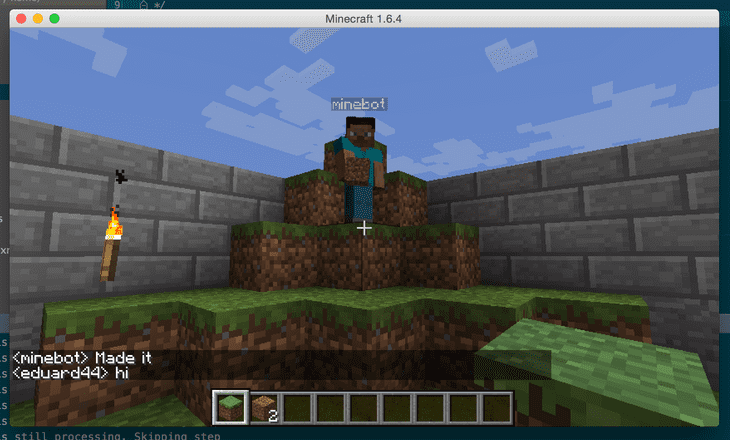

After building the components, I was able to make the agent perform simple tasks, such as finding a block, jumping, or navigating somewhere.

By making use of the task tree, I was able to create more complicated tasks composed of smaller tasks. Such as the task, which requires the agent to fetch materials first before building a column.

The conditions in which the agent will work are still more limited than I was hoping for. There are cases where the agent will get stuck navigating somewhere or unnecessarily placing blocks to get to a location where it can get more blocks.

This unwanted behavior is mostly due to the fact that the prebuilt navigation algorithms do not consider the state of the agent. Reimplementing the scaffolding and navigation algorithms inside the bot should allow for more efficient navigation that considers the current task at hand.

Demo

There are two videos showing progress on the agent logic:

- Video 1: In this video the agents ability to follow commands, navigation, and self-defense rules are tested.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Fk0kv0LM3g

- Video 2: In this video, the ability to build columns is tested, which is the most complicated task since it requires many subtasks to be performed. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1tqEAEHa7kc

Source code

The source code for the project is available online at: https://github.com/etcinit/minebot. Instructions on how to execute the agent are included in the README.md file

Conclusions and recommendations

While the agent is able to perform certain tasks, its functionality is still very limited. In order to build a more useful agent, I might need to write a larger amount of rules and tasks. However, the current agent should be able to provide a good enough foundation for writing more complex rules.

It would be interesting to explore genetic algorithms for allowing the agent to learn how to perform tasks. The main difficult seems to lie on connecting a genetic algorithm with the task tree.

I’ve recently been working on a Minecraft bot built in Node.js as part of my final project for my artificial intelligence class. The Minecraft-Node connection is possible thanks to a library called Mineflayer which acts as a Javascript bridge between Minecraft and Node.

So far the bot can do the following things:

- Stare silently at the last player who talked in the chat

- Pick up dirt blocks from a pre-set resource area

- Navigate around (using the Mineflayer-Scaffold plugin)

- Keep track of state using a Knowledge Base

- Respond to events through logic rules

- Execute tasks by priority and dependencies (Example: Go to resource site before digging, or prioritize fighting back from digging)

The final goal is to have the bot build a simple column it can climb at night so it can survive longer than a day, and possibly have it build other things during the day.

Demo:

Source code

Test it yourself or make your own changes: The source code is available at http://github.com/etcinit/minebot. It requires Minecraft 1.8 (not lower or higher) to work.

Laravel 5 introduces the concept of “bootstrappers”, which are classes whose sole purpose is to setup the application. This new layer of abstraction makes many of the initialization code of the application modular and portable, so if you want to replace or change how a part or the whole initialization process, you can!

Update: The behavior implemented in the fragment below is now implemented by default in the following commit 7b4e918. You can still use the code below to define your own custom logger

The following is an example of a bootstrap class that replaces the regular logging service, with a logger that uses daily files (keeps one different file per day automatically):

<?php

namespace App\Bootstrap;

use Illuminate\Log\Writer;

use Monolog\Logger as Monolog;

use Illuminate\Contracts\Foundation\Application;

/**

* Class ConfigureLogging

*

* Setup Custom Logging

*

* @package App\Bootstrap

*/

class ConfigureLogging

{

/**

* Bootstrap the given application.

*

* @param \Illuminate\Contracts\Foundation\Application $app

* @return void

*/

public function bootstrap(Application $app)

{

$logger = new Writer(new Monolog($app->environment()), $app['events']);

// Daily files are better for production stuff

$logger->useDailyFiles(storage_path('/logs/myapp.log'));

$app->instance('log', $logger);

// Next we will bind the a Closure to resolve the PSR logger implementation

// as this will grant us the ability to be interoperable with many other

// libraries which are able to utilize the PSR standardized interface.

$app->bind('Psr\Log\LoggerInterface', function ($app) {

return $app['log']->getMonolog();

});

$app->bind('Illuminate\Contracts\Logging\Log', function ($app) {

return $app['log'];

});

}

}Once the bootstrap is defined, you can override the $bootstrappers field on both the Http and Console Kernels:

/**

* The bootstrap classes for the application.

*

* @return void

*/

protected $bootstrappers = [

'Illuminate\Foundation\Bootstrap\DetectEnvironment',

'Illuminate\Foundation\Bootstrap\LoadConfiguration',

'App\Bootstrap\ConfigureLogging',

'Illuminate\Foundation\Bootstrap\RegisterFacades',

'Illuminate\Foundation\Bootstrap\SetRequestForConsole',

'Illuminate\Foundation\Bootstrap\RegisterProviders',

'Illuminate\Foundation\Bootstrap\BootProviders',

];NOTE: Laravel 5 is under active development. This method might not work on the final release. Also, once you override the $bootstrappers variable you need to make sure it stays up to date with Laravel’s code (at least while it is non-stable) since they could rename some of these classes.